Rosalie Fitzpatrick on fiction and cooking without allergens: writing, editing, best of lists, reading recommendations, books, mangas, movies, TV shows, comics, quotes and recipes. All recipes focus on allergen free cooking suitable for endometriosis and pregnancy: wheat, egg, cow's milk, rye, oats, soy, almonds, peanuts, red meat and gluten free. Also, most are seafood, alcohol, yeast and nut free. All other allergen exclusions vary per recipe.

Showing posts with label Publishing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Publishing. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

On judging good books and terrible books and the writing of either

There are good books, great books, entertaining books, life changing books, enlightening books, exciting books, world exploring books, whispering books, shocking books, horrifying books, repellent books and much more. All of them a good books. They're books to be read and to learn from. And then there are terrible books in which there is nothing but emptiness behind the words.

The question is: How can you tell them apart? Followed, of course, by these questions: What is worth printing or reading? How do we choose what to print and read? Are there many left unprinted that are worth reading? Are we able to find all the books worth our time or are there some rotting away in attics or lost to mass publication, distribution and mulching?

There is much to be said on the questions that follow and usually along the lines of: we aren't printing everything that's worthwhile, we're printing and reading a lot of trash, there are there so few people calling the shots on what becomes available to read, there are tonnes of books left unprinted that are interesting to read... so on and so forth. Essays could and have been written on many of these topics, addressing the pros and cons of publishing, of writing and or reading.

But the question for today is: How can you tell a terrible book full of emptiness from a good book, whatever its particular genre or style or 'flavour', as it were? It is a good question to answer given that I'm currently in the book recommendation business, if not reviewing. It is also one to ponder while reading manuscripts and assessing them for an agent. And even when writing a book of my own. Certainly, just because I put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard it doesn't mean that my work isn't full of emptiness. And how do I explain that a light-hearted piece isn't light for emptiness? The question does echo through so much. It is there when I buy books, when I choose what to read next. It is there when I scan mangas, when I look at movie covers on a lonely evening. It is there when faced with a library's worth of books and I stand about wondering where to start or if I shouldn't at all because there's something better elsewhere. It is there when faced with the choices educators hand my way and I wonder why I'm reading this old thing over again and not something else. It is even there when I grasp onto a book so I can walk down the street without thinking I've forgotten my mind or when I put the current selection close on the bedside table so I can sleep well at night. The question bears thought, I believe, as I have often been called upon to justify my thoughts, actions, choices, habits, attachments, writing style, imaginary worlds, genre choices, intellectual pursuits and judgments.

To me the answer is both fairly simple and deeply complicated, as all good things tend to be. The short and sweet answer reads like a greeting card: A good book makes you think and dwell within the covers as long as possible. Something of this sort. Or maybe an answer along the lines of ripples in the mind, echoes of thought and feeling, lingering attachments to what was found within the covers or even a life-changing work.

But the vague greeting card answers don't help much if you want to actually create a work that could be said to be a darn good book. Just how do you make people dwell on what's within the covers or feel any sort of mind-altering impact? Just how literary and serious must a writer be to create such pieces of great worth? Or better yet, is there a formula you can show me on how to do all of the above? What the above leaves the creative is a mass of confusion, nail-biting paranoia and uncertainty. It leaves the creative wondering if their work is justifiable or even worthy enough to be read at all? Maybe if all the spelling and grammar is correct then it could be read by at least someone, right?

Greeting card evaluations are useless. You can't provide a manuscript assessment with any of them. You can't answer why you chose one book over another with them. You can't justify your attachments either. No, you must produce more in-depth analysis and justify yourself clearly. Otherwise, one book is as good as another because every book reflects at least a little of the light that is life and if we're reading for those reflections then they are everywhere and in every book written by a human. And even by those written by non-humans, if ever we come across such a thing (I'd love to see such a day but that's just my mind off wandering again).

The longer and more complicated answer to the question of what is the difference between a terrible book and a good one is something you'll trip over nearly every time you ask the question "Why?" just after asking the question "What's your favourite book?". To each his or her own, really, as it depends on what is reflected, whether the reader sees it or not, whether it is a perfect or distorted reflection of their life experiences and whether the reflection is at all recognisable or understandable. This means that there's no perfect or best book ever written, just ones the majority find intriguing, comforting, illuminating, disturbing and life-altering and ones the majority just don't get.

"William Shakespeare!", you're thinking, because he addressed so much of what it is to be human. But then, so do many others in their dramas. "Chaucer!" for his ability to address our baser natures and reveal us for what we are. But then, there are thousands of lesser know writers about who constantly point out just how gritty, polluted and base humanity is - take Chuck Palahniuk for an example of a better known one. Chuck or Chaucer? Which works are better? Don't think on mass popularity or intellectual pursuits. Don't consider how many sold or lasting through centuries. Just the works. Side by side. Which are the best sets of work? There are likely many of you saying "Well Chaucer, obviously" while the others are muttering "But I've only read Chuck's and his works are more relevant to today". Between these two major players you are stuck in a deadlock. But if I tried to pitch my own work or a fellow unpublished writer's work into the mix against either or both (mine isn't a gritty-mode book but this is just for argument's sake so whatever) and asked the same question I believe the answer would be flat our Chaucer or Chuck, depending on which I or we are being judged against. Yet this answer could well be wrong.

All this is on how we value a book, how we perceive it due to culture and fashion. But perceived value and fashion doesn't actually make a book good. If it did we'd be lauding Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey rather than trashing them so thoroughly (after reading them or sometimes only after hearing of the content). Which means that such perception and fashionability, based on individual and mass opinion, do not a good book make and so all of those books that are printed and read on mass could well be trash. When working with equations you have to mind the faults. Or at least that's what I learnt while steadily failing math exams during year 9 for not paying attention to such a boring subject (my own perception but certainly not that of Hawking who I happen to admire, like so many others). Making up answers and saying they're definitely true for everyone just doesn't cut it.

And on that note, to add further complications to this mess of an explanation, there are many out there who love Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey and will hate you for trashing it in front of them, also finding themselves almost forced to justify themselves at which point they become indignant, angry, rebellious, argumentative and possibly violent. The need to justify stems from the feeling that the masses, or at least the person in front of them, has trashed everything about themselves that they saw reflected back at them in those books. Along with trashing their right to an opinion, their right to be heard and their hope to be understood.

Is publication an indication that the book is good and a lack of publication that the book is terrible? The answer to that is a resounding no. You may be thinking, "but I can't remember reading such a terrible book" but I will assume that is because most of the time you've chosen books to read as you've seen that there could be something in there for you. The experience is quite different when you're reading without that choice, just reading what's been plunked in front of you. At least you might remember experiencing something like this at school. Even then though, the books given to you were likely ones capable of reflecting a lot of life to a lot of people and so they were likely good ones, whether you paid them any attention or not.

What a mess...

So. I'd have to say that in short you're likely to write a good book as long as you put some of yourself in it. And you're likely to find a book good as long as you put in the effort to see something in it.

If you blinker yourself too much you won't see anything and all books will be terribly empty. Why? Because you are. If you remove the blinkers, or never set them in place (unlikely), then you are free to experience anything and see the reflections everywhere. And you become full enough to possibly, one day, be called wise.

If you fail to writing your thoughts, experiences, emotions, actions and sensations down then no-one can see any of it within your book. Being literary isn't required. Being serious isn't required. Slugging people over the head with a long fictional argument on a particular subject and ending it with a moral or definitive answer isn't required. Being human and conveying your humanity is. Fill the pages with it however you like, in whatever style you like and using characters born of yourself. Readers will see you and see themselves and your work will be good.

The equation here isn't so faulty. A terrible book is one written by a blinkered and empty person. There's no substance, no life, within or behind the words. No meaning behind the actions of characters. No resounding cause and effect within the world written. This lack is easily felt, whether a book has been published and approved of or not, and it is because of this that the book quickly fades away.

Monday, April 9, 2012

Types of books, book binding and book sizes

Fiction or non-fiction, books come is many sizes, shapes, bindings and files. Some I've known, some I've read and some I haven't heard the name of even though I've sold them so I thought I'd lay them out for you. It is interesting to see which styles have disappeared over humanity's writing history.

The Tablet

Tablets were what we originally wrote on when it wasn't on walls or in caves. Stone, mud and clay were often used though stone is the most durable and that's why grave stones are by-and-large made of stone and concrete rather than wood or clay. Tablets are still in use but only rarely outside of the burial industry.

Scroll

This is a declaration scroll so it is a touch fancier than most old scrolls. Scrolls were first used after the invention of papyrus: a thick paper-like material made from the woven stems of the papyrus plant. A scroll was a sheet of papyrus or later paper curled in on itself, either from one side or both, with or without rollers. The papyrus or paper was rolled for portability and storage. Once widely used they are now mainly used in traditional practices like religious ceremonies, royal weddings etc. or in plays, for extra-classy invitations or for architectural designs (rarely rolled nowadays but still down).

Codex

Many books in one. Or, many scrolls (single books) bound together. The leaves are all of uniform size and are bound along one edge. The codex is the early beginnings of what we now generally call a book. It gained widespread popularity in the early Christian communities, possibly for cultural identification purposes, as most other types of communities still preferred scrolls.

Manuscript

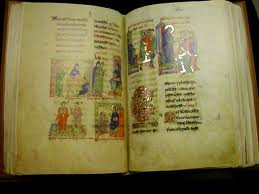

When parchment became more popular than papyrus do to availability problems (political not environmental or agricultural) manuscripts were created. Almost all books were manuscripts copied by hand, making them expensive and comparatively rare. They were most commonly found in monasteries, papal libraries or in the property of royalty. If varied spelling and stylised writing isn't hard enough to read, spaces between words weren't commonly used before the 12th century. Vellum could be used instead of parchment. Only in Judaism is scribing manuscripts still widely done. According to custom, the Torah scroll can only be reproduced by hand. Manuscripts are otherwise extremely rare these days due to the labour involved and the high level of skill required.

Quarto

Octavo

DuoDecimo

Sextodecimo

The paper is folded four times to form 16 leaves or 32 pages. It stands up to 6 ¾" (ca 15 cm) tall.

Folio

Stands up to 15" (ca 38 cm) tall. Commonly used in the printing of early plays.

Elephant Folio

Stands up to 23" (ca 58 cm) tall. Best used in photography or art books.

Atlas Folio

Stands up to 25" (ca 63 cm) tall. Large and perfect for detailed illustrations but not so good for portability. Best used in reference material.

Double Elephant Folio

Codex Gigas

This is the Codex Gigas and it is 92 × 50 × 22 cm. It is the largest extant medieval manuscript in the world.

Booklet

Anything between 3 (ca 8 cm) tall - 5 ¾" (ca 13 cm) tall can be called a booklet. Often include less than 50 pages and are used mostly in business or ceremonies.

eBook

The book is a digital file that can be transferred or carried on various readers, digital storage devices and computers.

The Tablet

Scroll

Codex

Manuscript

Quarto

In printing and binding, the paper is folded twice, forming four leaves or eight pages approximately 11-13 inches (ca 30 cm) tall.

The most common size for hardcover books printed today. The paper is folded three times into eight leaves or 16 pages up to 9 ¾" (ca 23 cm) tall. This is the type of book most authors hope to be printed in one day and when they do they'd like a first edition copy and a new ambition.

DuoDecimo is a size that falls between Octavo and Sextodecimo. It stands up to 7 ¾" (ca 18 cm) tall.

Folio

Elephant Folio

Stands up to 23" (ca 58 cm) tall. Best used in photography or art books.

Atlas Folio

Stands up to 25" (ca 63 cm) tall. Large and perfect for detailed illustrations but not so good for portability. Best used in reference material.

Double Elephant Folio

Stands up to 50" (ca 127 cm) tall. Ridiculously large but great for detailed illustrations like this. As with the Atlas Folio this type of book is best used for reference material.

This is the Codex Gigas and it is 92 × 50 × 22 cm. It is the largest extant medieval manuscript in the world.

Booklet

Anything between 3 (ca 8 cm) tall - 5 ¾" (ca 13 cm) tall can be called a booklet. Often include less than 50 pages and are used mostly in business or ceremonies.

eBook

The book is a digital file that can be transferred or carried on various readers, digital storage devices and computers.

Labels:

Atlas,

Book Binding,

Book Sizing,

Booklet,

books,

eBook,

Fiction,

Folios,

Manuscripts,

Printing,

Publication Methods,

Publishing,

Quartos,

Scrolls,

Tablets,

Types Of Books,

writing

Thursday, March 1, 2012

Writing on human skin part II

For my book I had to look up whether there was a special name for the vellum made of human skin rather than animal. As it is, I haven't yet found that out as I was waylaid by morbid curiosity after running across this information.

A long and sometimes gruesome history lies behind the writing on human skin. My previous post was on the tattooing of quotes, the lighter side of writing on human skin. This is the darker side.

In the history of use of human skin and tissue for writing you will run across the Nazis, Ed Gein, Marquis de Sade and Saddam Hussein (wrote in blood). Anatomy textbooks were often bound in skin as were erotica books. Also, judicial recordings were frequently bound in the skins of the condemned. On the most acceptable side, newly popular or informative texts bound for longevity had human skin covers, complete with inscriptions, that often resulted from a voluntary donor (requested in a Will).

Anthropodermic bibliopegy: the practice of binding books in human skin.

Autoanthropodermic bibliopegy: volumes

created as a bequest and bound

with the skin of the testator

(If you wrote in your Will that you wish to have your skin used for binding

books your skin may well have been used for just that).

Notes:

Only one of the below skins may have been taken from a live human. The rest have been taken after death, two likely with consent.

The practice of using human skin to bind books was not an underground or distasteful practice for much of its history. It just wasn't common practice as a great deal of work is involved and skins needed to be obtained. In recent history there have been horrific cases of skins being obtained unlawfully and sometimes from live humans, leading to the outrage most now feel at seeing such bindings. I will not rule either way but rather show you a few examples. You can make up your mind re moral, ethical and sanitary issues. Above all though, knowledge of this practice should never be forgotten as it is one of the practices that can lead to human atrocities. Anything with such potential should not be forgotten in case we must face and fight it again.

Practicarum Quaestionum Circa Leges

Regias Hispaniae

Skin from Jonas

Wright, 1632.

Last page inscription: “The bynding of this booke is all that remains of my deare friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632. King btesa did give me the book, it being one of poore Jonas chiefe possessions, together with ample of his skin to bynd it. Requiescat in pace.”

Last page inscription: “The bynding of this booke is all that remains of my deare friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632. King btesa did give me the book, it being one of poore Jonas chiefe possessions, together with ample of his skin to bynd it. Requiescat in pace.”

A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole

Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors, Garnet A Jesuit and His

Confederates

Skin from Father

Henry Garnet, 1606.

Latin

cover inscription translates as: “Severe penitence punished the flesh.”

The book is about the Gunpowder Plot and Father Henry Garnet was a co-conspirator to Guy Fawkes.

The book is about the Gunpowder Plot and Father Henry Garnet was a co-conspirator to Guy Fawkes.

People believe they can see is face in the cover...

Red Barn Murder

Judicial Proceedings

Skin from William

Corder (The murderer. Also, his

skeleton became a teaching aid in the West Suffolk Hospital), 1828.

Inscribed “The Binding of this book is the skin of the

Murderer William Corder taken from his body and tanned by myself in the year

1828. George Creed Surgeon to the Suffolk Hospital.”

Narrative of the Life

of James Allen, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove,

the Highwayman, Being His Death-bed Confession to the Warden of the Massachusetts State Prison

Skin from James Allen, 1837.

Cover inscription “Hic Liber

Waltonis Cute Compactus Est” translates to “This book by [Allen] bound in his

own skin.”

The Poetical Works of John

Milton

Skin from George

Cudmore (unrelated and unknown to John Milton – this was all the work of a

bookbinder/seller who stole the skin of the hanged murderer George Cudmore), 1852.

El Viaje Largo by

Tere Medina

Skin from

Unknown, 1972.

Inscription:

“The cover of this book is made from the leather of the human skin. The

Aguadilla tribe of the Mayaguez Plateau region preserves the torso epidermal

layer of deceased tribal members. While most of the leather is put to

utilitarian use by the Aguadillas, some finds its way to commercial trade

markets where there is a small but steady demand. This cover is representative

of that demand.”

Other books that

were bound in skin:

Samuel

Johnson’s Dictionary, 1818:

skin from James Johnson (unrelated).

Virgil’s

Georgics: skin

from Jacques Delille (translator of Virgil’s Georgics – skin stolen when he was

lying in state).

Leeds, England Ledger, 1700’s: skin from Unknown (though suspected to be a

victim of the French Revolution).

Terres du Ciel, 1882: skin unnamed French

Countess (She died young from

tuberculosis but before she did she asked the book binder Flammarion to use her

skin to bind a copy of his next book.)

Cover inscription: “Pious fulfillment of an anonymous wish/ Binding in human skin (woman) 1882.”

Cover inscription: “Pious fulfillment of an anonymous wish/ Binding in human skin (woman) 1882.”

De Humani Corporis Fabrica libri septem

by Vesalius, 1543: skin from

Unknown.

Lincoln the Unknown by Dale

Carnegie: several copies covered with jackets

containing a patch of skin from an unknown male African American. Skin patches

were embossed with the title.

Justine et Juliette by Marquis de Sade: tanned skin from Unknown female’s breasts.

Labels:

Binding,

Book Binding,

Book Making,

books,

Convicted Criminals,

Fiction,

Handmade Books,

History,

History Of Writing,

Human Skin,

Publishing,

Skin,

Traditions,

Wills,

writing,

Writing On Skin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)